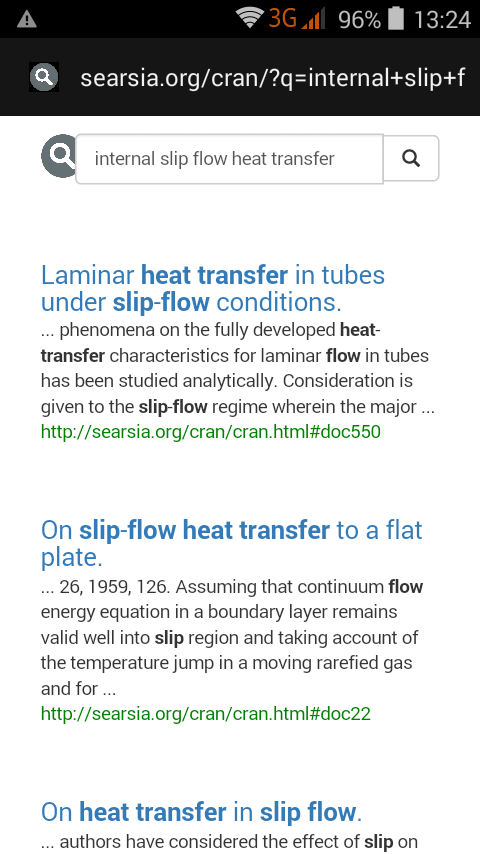

Information Retrieval has come a long way since Cyril Cleverdon conducted his famous Cranfield experiments on 1400 paper abstracts in the 1960’s. At the time, searching the massive 1.6 megabyte Cranfield collection was a big deal. Today, we routinely take pictures that are much bigger, and even a crappy smart phone can search the data in milliseconds in the web browser. Seriously! Here’s a screen shot of the Oukitel OriginalOne (a smart phone that has 512 MB RAM and costs about € 50) searching the Cranfield collection in its Android 4.4.2 default browser. It’s the phone that does the actual searching:

|

Searching Cranfield on your phone

A full-fledged search engine in the browser

Search engines use inverted files to quickly search in lots of documents. An inverted file operates much like the index in the back of a book that lists for each important term the pages that describe the term. Similarly, an inverted file lists for every word the web pages that contain the word. This allows a search engine to quickly select the pages for your query.

A full-fledged inverted file search engine for the browser is provided by Sphinx, the Python Documentation Generator. While generating the documentation, Sphinx also generates a JavaScript file called searchindex.js which contains the inverted file. Before searching the documentation, the file is downloaded to the browser to provide search results in only milliseconds.

A similar approach is taken by Lunr.js. Lunr is completely written in JavaScript. It provides indexing functionality, a powerful query language, and it runs both in the browser as server-side with node.js. Lunr’s standard mode of operation builds the entire index in the browser, but it also offers a way for downloading pre-built indexes similar to Sphinx.

Another remarkable example of an inverted file search engine for the browser is JScene, a proof-of-concept search engine developed by Jimmy Lin. Lin (2015) pushed JScene to its limits by searching 1.1 million tweets in milliseconds on a Mac-book Pro (containing an i7 processor and 16 GB of RAM). Although awesome from a technical perspective, searching that many documents is not yet practical. JScene took more than 10 hours to create a massive 1.8 gigabyte index from 140 megabytes of tweets. The pre-built index would need to be downloaded to the browser before the querying can start (and most certainly would crash our crappy smart phone).

So, while searching millions of pages might not be practical yet in the web browser, searching less than a few thousand pages certainly is. This is useful for the many smaller web sites that are out there: personal blogs, sites with software documentation, sites of small and medium-sized enterprises, and yes, the great Cranfield collection.

Searsia’s linear search in the browser

Searsia is all about delegating search to other search engines. So why would Searsia support in-browser search? The reason is that in practice, the search quality of some engines in a federated search engine might not be that good. In such cases, Searsia provides the possibility to add the “rerank” attribute to a search engine definition, indicating that Searsia should rerank the results returned by the search engine. This works particularly well if the low-quality search engine provides a large result set, for instance the top 500 most recent news events.

Reranking might be done server-side (by searsiaserver) or in the browser (by searsiaclient). In both cases, building an inverted index is useless, because the low quality search engine might provide different low quality results for each query. Instead, Searsia simply scans over each result to output a reranked top X of high quality search results to the user. Constructing the inverted file would be much more costly: In addition to scanning each document it has to do a complete sort of all term-document pairs.

As an interesting side-effect of Searsia’s in-browser linear search approach, users can create a static Searsia search result file, like a “search engine” that always gives the same search results. Obviously, the quality of search engines get not much lower than that. However, if we now define a search engine with the rerank attribute that always takes the static results, then the resulting search engine is pretty good, especially if all pages are included in the static search results. This is how to make the Cranfield search demo: The search engine definition and search results are defined in a single configuration file cran.json.

Private search

In-browser search comes with an interesting benefit that solves some of the privacy concerns of search engines that we discussed in a previous blog post. If search happens inside your browser, then your query does not need to leave your private machine, ever. This way, the site owner cannot learn what you searched for, and you can safely search for private information concerning for instance your health, sexual preferences, or financial situation.

Private search using Searsia is demonstrated by NLnet Search. Here, the client uses URL fragments (the part after the hash symbol #) to encode the queries. That part of the URL is not send to the web server, so NLnet will not find out what you search for. To experience private search, do a single search on NLnet, and then turn off the wifi on your phone or laptop: Searching should still work without an internet connection. Of course, once you click on a search result, the site will get some indication of what you searched for, but at least your queries are not leaked to the site owners. No chance they end up in some autocompletion feature.

Conclusion

In-browser search engines are feasible for small collections of up to a few thousand pages. They are easy to deploy and work on static web sites that do not handle any server-side processing. Their functionality is great from a privacy-perspective. Your browser downloads an inverted index or a static search result file, and it searches inside your own machine. The site that you are searching will not find out what you searched for.

Please note, Searsia’s in-browser search is still experimental and largely undocumented. The implementation in the v1 branch on Github is much better than the master branch, and it will be further improved in the near future. We will provide more guidelines and documentation once we release version 1.0.0 of Searsia. In the meantime, contact us if you need help trying out Searsia’s in-browser search.

References

- Cyril Cleverdon, Wikipedia.

- Download the Cranfield collection, University of Glasgow.

- Inverted index, Wikipedia.

- Sphinx, Python Documentation Generator.

- Lunr, Welcome to Lunr.

- JScene JScene Demo.

- Jimmy Lin. Building a Self-Contained Search Engine in the Browser Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on the Theory of Information Retrieval (ICTIR), pages 309-312, 2015.

- NLnet Search